Three ways to spoil a discussion

Good discussions can improve our understanding of the world, clarify our values, and develop the concensus required for taking action as a group. Bad discussions aggravate, alienate, and confuse. Great products, businesses, and policies rest on a foundation laid in good discussions.

Discussions are not debates. Debates are for the benefit of an audience and something you try to win in the eyes of that audience, regardless of what is true or right.

I have no fool-proof recipe for good discussions, but I have noticed three mistakes that spoil them:

- Using ill-defined words

- Accepting arbitrary beliefs

- Confounding truth and preference

Avoiding these mistakes is not rocket science, but it does require discipline, precision, and equanimity.

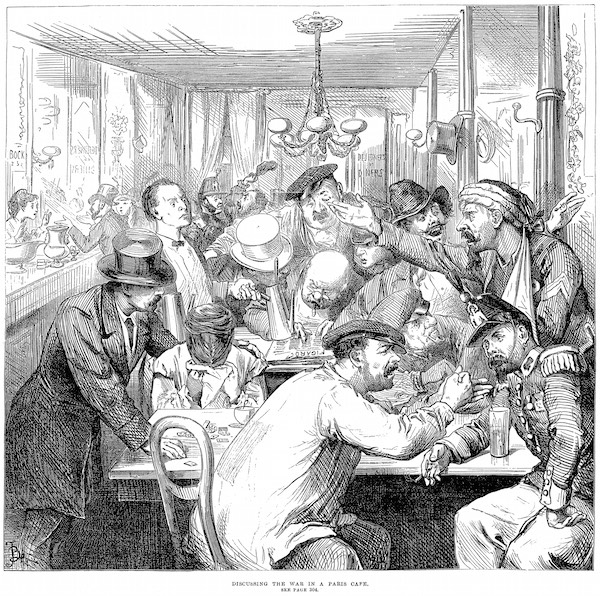

Discussing the War in a Paris Café by Fred Barnard appeard in Illustrated London News on 17 September 1870. Source: Wikipedia

Using ill-defined words

A discussion is futile if participants use the same word to mean different things. No common understanding can develop and progress will stall.

For example, “liberal” is commonly used both to refer to a proponent of a big, high-tax government and a proponent of a small, low-tax government. One reason for this confusion stems from the difference between economic liberty (low taxes, free markets) and social liberty (unconstrained lifestyle). The political left is traditionally considered socially liberal and economically regulated (big, high-tax government) and the political right is traditionally considered socially regulated and economically liberal (small, low-tax, government). Another reason for confusion is that a “Liberal” (with captial L) usually refers to a support of the *Liberal Democratic Party" in the United States. Thus, in a discussion about politics we need to be precise about what we mean by “liberal”.

There is no common term for those who are both economically and socially liberal, but they are sometimes referred to as “classical liberals”.

Defining terms takes time, but it pays off and you don’t have to do it all up front. Ask for clarifications in the course of a discussion: What do you mean when you say “simple colours”? A rule of thumb is to avoid redefining words; check dictionary definitions and other authoritative sources. You might want to give a word a more precise meaning than is common, but avoid contradicting authoritative usage.

Accepting arbitrary beliefs

The second mistake is to think that all beliefs are created equal. Your degree of belief in a statement refers to your assessment of the probability that the statement is true. This degree of belief lies between 0 (certainly false) and 1 (certainly true). We form our beliefs based on our prior beliefs and the evidence we observe. I call someone rational when they strive to form beliefs that are consistent and reasonable given the evidence they observe. Two rational people may reasonably disagree about what is true if they have observed different evidence.

For example, most adults have a degree of belief in the existence of Santa Claus that is close to 0 and a degree of belief in the earth being round(ish) that is close to 1. If, however, we were to observe a sled with a white-bearded man in the sky, pulled by flying reindeer we would increase our degree of belief in Santa Claus (unless we had a good alternative explanation for the observation).

Beliefs lie at the heart of discussions about what is true. If people arbitrarily assign belief, there is no way for them to agree on what to believe given some set of observations. If, on the other hand, everyone strives to form consistent beliefs, then the group can incorporate each other’s experience, observations, and reasoning to form beliefs that are more accurate than those of any individual participant.

How to form consistent beliefs is formalised in Bayesian probability theory. That is a fascinating topic and the foundation of scientific reasoning, but you don’t need a deep grasp of it. An understanding that beliefs should be based on evidence and consistent reasoning will suffice for most discussions. In fact, many scientists do great work despite being unfamiliar with formal Bayesian inference.

Confounding truth and preference

There are actually two kinds of discussions:

- Discussions about what is true (how the world behaves).

Most people (including many, if not most, philosophers) believe that there is an objective truth. If you don’t accept that, I think you’ll struggle to have productive discussions with other people.

- Discussions about what is preferred (what is good and bad).

Discussions about what is true try to answer questions such as: Will a minimum wage lead to higher unemployment? or Are carbs unhealthy? Such discussions are about the evidence participants have observed and how they reason about how things behave and the result is that each participant updates their beliefs, taking new input into account.

Discussions about what is preferred explore questions such as: Should same-sex marriage be legal? and Should we eat pizza tonight? Such discussions can be about finding compromises that allow a group to take effective action together or about expoloring if an individual’s set of preferences is internally consistent.

A set of preferences can be inconsistent either by having logical contradictions – “abortion should be legal and all fetuses have an absolute right to life” – or by having practical contradictions – “abortion should be illegal and no unwanted babies should be delivered”.

Practical condradictions are particularly difficult to identify because they depend on our beliefs about what is true. That means we need to intersperse discussions about truth (how the world behaves) with discussions about preference (what is good and bad). It is all too easy (and common) to instead confound the two by stating a preference for a course of action that you believe will result in the outcome you actually want.

For example, if someone simply states a preference for invading another country, you don’t have much room for discussion. If, on the other hand, they say they prefer the population of a country to live under a rule of law instead of a dictator and they believe the best method to achieve that is a military invasion, you can discuss both their preference and the beliefs that make them conclude that an invasion is the best way to achieve the desired outcome.

So we must clearly distinguish between truth and preference in order to have productive discussions. Doing that well takes discipline and practice, but it can be the difference between conflict and cooperation.

Conclusions

Good discussions challenge our beliefs and preferences, but in return improve the accuracy of our beliefs, identify inconsistencies in our preferences, and find compromises that allow us to take action together.

By using well defined words, by forming rational beliefs, and by clearly distinguishing between our preferences and our beliefs, we increase our chances of having good, productive discussions.

I sometimes think of discussions as a form of exploration in the world of ideas which, just like the exploration of our physical world, can be hard and uncomfortable, but also provide the excitement and joy of new discoveries.

The collaborative aspect of discussions means that the more you discuss with someone, the more understanding you get for each other’s language, beliefs, and preferences. That means you can cover ground faster than if you frequently had to stop to define terms or understand each other’s beliefs. That is why discussions with friends or colleagues can be particularly satisfying.

So, keep an open mind, be patient, and eagerly admit shortcomings.

Bon voyage!

Thanks to Jan Sramek and Emily Rookwood for giving feedback on drafts.

Further Reading

Paul Graham, How to Disagree, http://www.paulgraham.com/disagree.html ()

Paul Graham, Keep Your Identity Small, http://www.paulgraham.com/identity.html ()

E. T. Jaynes, Probability Theory: The Logic of Science (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, )