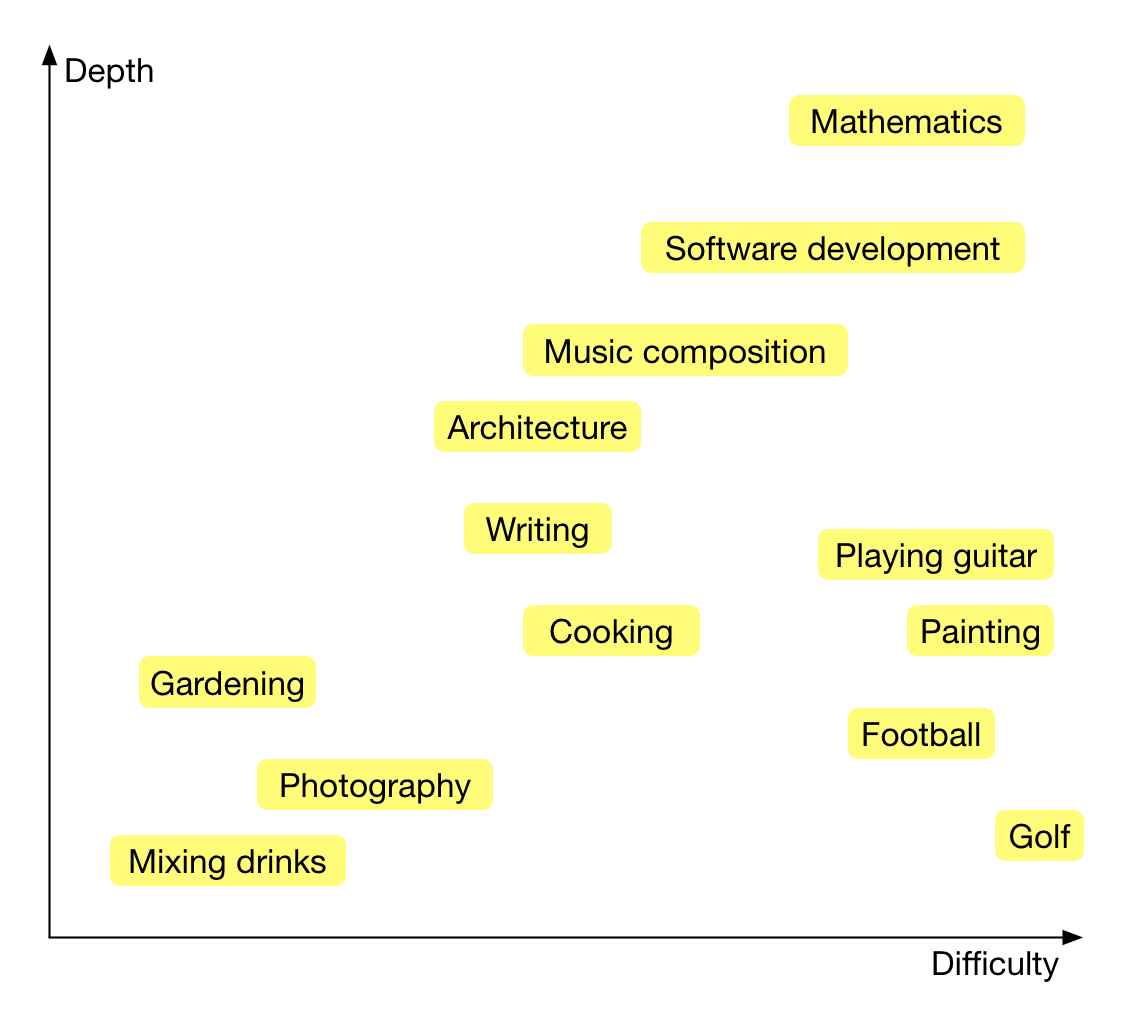

Depth and difficulty

When pondering how much time and effort it takes to become good at something, I’ve started to think of activities in terms of depth and difficulty:

- Depth: the amount of theoretical or conceptual understanding required to consistently produce great results.

- Difficulty: the amount of practice required to develop a high level of skill.

Deep, difficult activities are not intrinsically better than shallow and easy ones. They are different, with different trade-offs; their value is subjective.

Subjective sketch of depth and difficulty for different activities. This compares activities performed at their best. The average professional composer is likely using more theory and skill than the average professional software developer simply because competition for composer jobs is higher than for developer jobs.

Depth determines how much time and effort you’ll have to spend studying literature and learning from the best performers. By definition, you can’t figure out all useful patterns behind deep activities yourself in a reasonable time. Deep subjects tend to have room for you to improve yourself over decades without reaching intrinsic limits.

Difficulty determines how much time and effort you’ll have to spend on deliberate practice and drills in order to get good. Some people consider difficulty a fun challenge, others a necessary evil. Different activities require different speed and precision relative to normal human abilities; gardening is sensitive to neither speed nor precision; tennis is sensitive to both speed and precision; painting is (usually) sensitive to precision but not speed. It is the amount of speed and precision required that determines how difficult the activity is. In competitive activities, the required speed and precision are pushed to their limits. In non-competitive activities, it depends on the domain.

If you choose a deep and difficult hobby, you should expect it to take years or decades to reach a skill level comparable to that of famous practitioners. It will also require both extensive study and diligent practice to get there. You only have time to get good in a small number of these in a lifetime.

In contrast, we can expect to get really good at shallow and easy activities with comparatively little effort. If we value the outcome of these activities, they can have a great return on investment and allow us to gain some breadth of skills even if we spend most of our time on deep and difficult activities.

If mastery makes us feel good and if output value is a superlinear function of ability (I believe it usually is) we should focus our time and effort on no more than a small number of deep and difficult activities and complement them with a larger number of shallow and easy activities.