Deliberate practice

Ericsson’s excellent and highly readable article The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance from 1993 started what in the last 5 years or so has bubbled up to the surface

Gladwell’s Outliers played a key role in popularising deliberate practice and the 10,000 hours meme, but I’m not a fan of Gladwell’s style.

.

Deliberate practice is training on the edge of your ability with the sole aim to get better. It’s not the same as performing; playing a game of chess, playing a round of golf, or solving a familiar type of mathematics problem are not examples of deliberate practice. Attempting 5 different openings in chess to figure out their strengths and weakness, hitting 300 golf balls with your 5 iron to get as close to the 150m sign as possible, or trying different solution strategies on a known mathematical problem are examples of deliberate practice if done with care and deliberation.

Ericsson found that our ability to do something – sing, play football, read, negotiate, write – is proportional to how much deliberate practice we have had. That is a magnificent result with far-reaching implications; first of all, natural talent is largely overrated. If you think about it, that’s not surprising. The neural connections in our brain determines our performance. They are shaped by evolution (genetics) and environment. Even though being a musician is a great way to get laid (or so I hear), evolutionary pressures have not favoured piano virtuosos. They have, however, favoured the ability to learn whatever is useful at the time; thus, our brain has been optimised for learning.

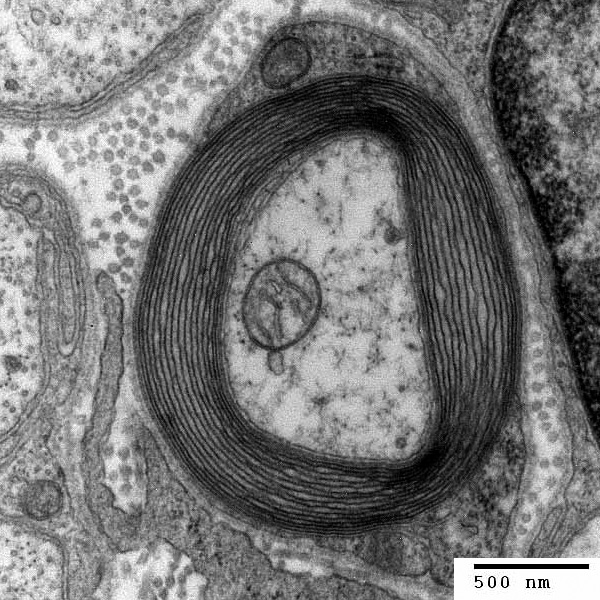

Biologically, it turns out, deliberate practice wraps neural connections layer by layer with a kind of insulation called myelin that strengthens the connections and speed up the signals they carry. This is what a cross-section of a myelin wrapped nerve fibre looks like:

Cross-section of an axon wrapped in several layers of myelin. Source: Wikipedia

When a neural pattern “lights” up, it is strengthened. That’s why deliberate practice works; and that’s why there are no shortcuts.

Understanding deliberate practice is important and rewarding. Coyle’s Talent Code and Colvin’s Talent Is Overrated are two of several recent books on the topic. Coyle’s exploration is lucid and engaging. With concrete examples from a variety of fields – tennis, football, writing, and music – he gives an intuition and argues convincingly for the generality of deliberate practice. The book covers the foundations (Deep Practice), how people come to do it (Ignition), and what makes for effective teaching (Master Coaching). It is an excellent introduction to the topic.

Addendum: Though I still find The Talent Code excellent, my recommendation for an introduction to the topic is now Ericsson’s Peak, published in 2017.

References

Ericsson, Krampe, Tesch-Römer, "The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance" Psychological review (American Psychological Association, )

Daniel Coyle, The Talent Code: Greatness Isn’t Born. It’s Grown. Here’s How. (New York: Bantam, )

Geoff Colvin, Talent Is Overrated: What Really Separates World-Class Performers from Everybody Else (New York: Portfolio, )

K. Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool, Peak: How all of us can achieve extraordinary things (London: Vintage, )